As part of my obsession with the seminal Chinese blockbuster game Black Myth: Wukong, I’ve spent countless hours studying Chinese literature, language, and culture to better appreciate the rich lore and context of the story.

The heart of Black Myth: Wukong is a continuation of the fantastical events of Journey to the West, one of the most influential works of literature in world history. The game, which has already sold over 20 million copies since its August release, is equal parts a passion project from the developers and a groundbreaking for China in the AAA game industry. It’s hard to overstate what this means for Chinese people, all of whom grew up on these legends, yet have never before experienced a game so dedicated to them.

Since the first trailer was released over four years ago, I’ve gone on a journey of my own, in the hopes of being able to appreciate the entire game in Chinese. I knew this would be no small undertaking, given the fact that the source text, as well as the game, are in a combination of literary prose and classic poetry (think Shakespeare × the King James Bible).

Furthermore, I began from the reading comprehension and character recognition of an elementary schooler, since I barely studied or used the language growing up.

Thus, I’ve found it immensely challenging, yet rewarding, to return to my roots and develop the skills necessary to achieve this goal.

This post serves as a record of my learning process, as well as a guide for other novice language learners seeking to immerse themselves in the refined beauty of Chinese literature.

Classical vs Vernacular Chinese

It’s often described that there are two forms of written Chinese: Classical, or Literary, Chinese (文言文), and a Vernacular Chinese (白话文).

Classical is a highly concise but now-obsolete style that was used for thousands of years in all formal contexts. Vernacular, which is in present use, gained traction in the early modern period via novels meant for the general public.

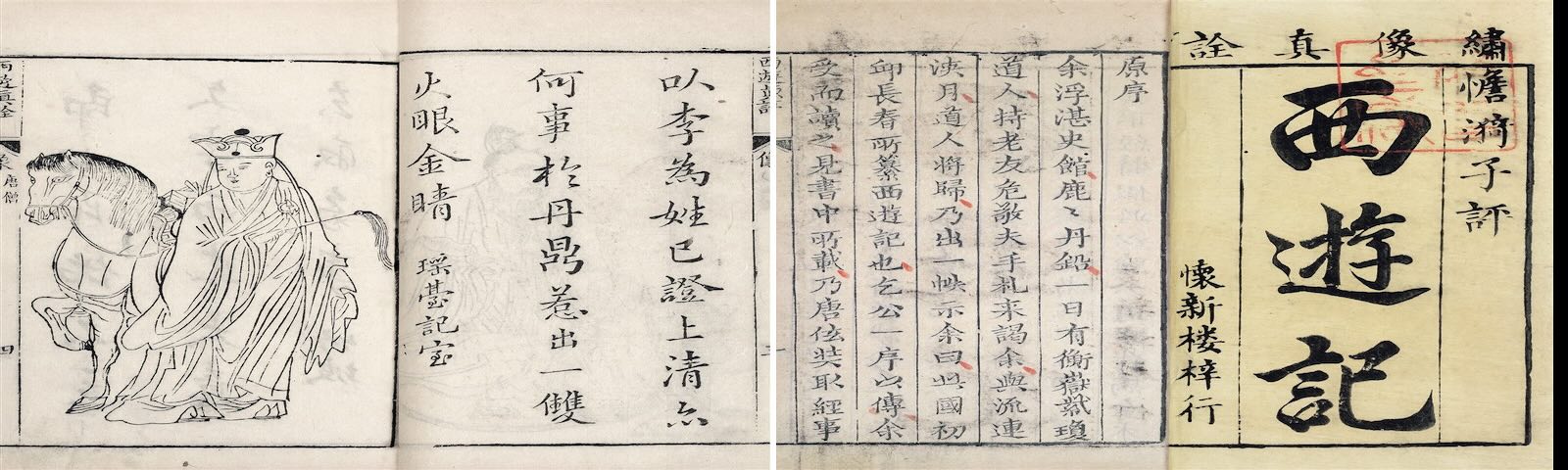

Journey to the West, published in 1592 by Wu Cheng-En, is considered one of those novels. However, I’d characterize it more as a blend of the two versions. The prose, while more parseable than Classical Chinese, maintains a scholarly and courtly tone that draws heavily on Classical language. This makes sense, given its setting in the 7th century Tang dynasty, and its subject matter of celestial immortals, demons, and religious pilgrimage. The text also intersperses lengthy stanzas of poetry for embellishment, which naturally employ Classical structures. The result is eminently readable, yet still exquisite, elegant, and wondrously descriptive.

As you might expect, BMW spares no effort in its faithfulness to the novel. All the dialogue, flavor text, and lore are written in the same half-Classical, half-Vernacular style, that I will call literary prose for the remainder of this article.

So, how do we go about learning literary prose? Here’s what I did:

Context, context, context

Not strictly about language learning, but I believe that, to understand a work like BMW, you need to understand its context.

Largely for fun as well as education, I started by rewatching the 1998 cartoon version of Journey to the West that I recalled from my childhood, while reading Anthony C. Yu’s abridged translation The Monkey and the Monk. This gave me a foothold for the story elements.

Then, before even attempting the source text, I skimmed some full synopses, reduced-difficulty versions, and relevant vocab lists, familiarizing myself with common names and words. All these served to make the initial encounter with the original work less daunting.

Memorizing characters and words

Despite the tens of thousands of unique characters in Chinese, you might be surprised that 98% of standard modern text, such as newspapers, use only 2000 of them. But that glosses over so much — you need to know the many two-character words and four-character idioms that can be formed from that set, along with the grammatical structures. 98% character recognition sounds like a lot, but is often only enough to get the gist of every sentence, while the nuance is much harder to extract.

And in Classical Chinese, the situation is even more complex. One major difference from modern Chinese is that the author will express words with just one character that has multiple meanings, rather than the unambiguous two. So, knowing a character may not even be enough — you need to know all the possible definitions, many of which have fallen out of common usage. Trying to unravel the resulting terseness can be like guesswork. Additionally, it heavily uses all sorts of strange pronouns and means of address, some of which are unclear as to who/what they’re referring to.

But firstly, expanding vocabulary and character recognition is a necessary starting point. Around 2500-3000 characters is enough to largely grok the prose in BMW and Journey to the West, but the most classical/archaic bits and the poetry would require 4-5000 characters for a careful reading.

I use Anki for memorization, which many learners will be familiar with. It’s a free flashcard app that uses spaced repetition, with frequency of each card adjusted based on how difficult you find it.

Other language learning tools

OCR

A good Optical Character Recognition (OCR) tool is a must when trying to translate on-screen text in videos or photos. On desktop, DeepL works amazingly for me, allowing me to take a partial screenshot of some text and translate it via a single keyboard shortcut. To OCR mobile screenshots, Papago performs the same purpose, but in multiple steps, because you first need to take a screenshot and then upload it to the app. Both are better than Google Translate because you can select the text after the OCR detection, allowing you to copy-paste it into, say, Anki.

Browser Extensions

If you’re a Simplified Chinese learner like me, the New TongWenTang Chrome browser extension allows converting web pages between Simplified and Traditional.

And you might already know the Zhongwen plugin, which translates words as you hover over them.

Video translating

On Youtube and Netflix, Language Reactor is an extension that shows the Chinese and English subtitles at the same time, while allowing you to pause after every voice line, navigate lines, and translate on hover.

Common patterns

Now, here’s a cheat sheet of some of the common patterns in literary prose that you might encounter on a first reading.

There’s many other resources online that provide a deeper or more comprehensive study of Classical Chinese, so I’ll restrict myself to simpler forms that are commonly used in BMW and Journey to the West.

Particles and adverbial phrases

| Word | AKA | Translation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 之 zhī | 的 | a possessive | |

| 与 yú | 和 | and, or with | |

| 此 cǐ | 这 | this; these | See next two rows |

| 此乃 cǐ nài | 这是 | this is | |

| 如此 rú cǐ | 象这样 | like this; like so | |

| 却说 què shuō | as we were saying; now the story goes | Literary particle at the beginning of a story, used to resume narration from where it was left off | |

| 则 zé | instead | Used to connect contrasting phrases | |

| 而 ér | then; and; but | Used to connect related or contrasting words | |

| 若 ruò | 1. 象; 似乎 2. 如果 |

1. like; as if 2. if; supposing |

|

| 宛若 wǎn ruò | 象 | to be just like | |

| 亦 yì | 也 | also | |

| 遂 suí | 然后 | then | |

| 致 zhì | to cause/result in | ||

| 尚 shàng | still; yet | ||

| 至 zhì | 到 | to; until | Ex. 至今 (until now) |

| 所 suǒ | that which is | Ex. 所吃的 (that which is eaten) |

Questions/Rhetoricals

| Word | AKA | Translation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 奈 nài | how; why | Expresses frustration and futility. Commonly seen: 1. 无奈 (to have no alternative) 2. 奈何 (what can be done?) |

|

| 岂 qǐ | 怎么可能? | how? | Ex. a common exclamation 岂有此理 (how can this be?; preposterous!) |

| 何 hé | why not | ||

| 如何 rú hé | 怎么样? | how about this/that? | |

| 不妨 bù fáng | 为什么不? | why not? |

Particles for emphasis/embellishment

| Word | AKA | Translation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 矣 yǐ | 了 | a final particle | |

| 也 yě | emphatic final particle | ||

| 哉 zāi | 吧 | emphatic final particle |

Pronouns/Forms of address

Ancient China had no shortage of words to refer to others or oneself, especially in self-deprecating fashion.

| Word | AKA | Translation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 其 qí | 1. 的 | 1. a possessive, like his/hers/its/their 2. it (refers to something preceding) |

Can have many different uses, but often one of these |

| 斯 sī | 这 | this | |

| 吾 wú 俺 ǎn |

我 | I/me | |

| 卑 bēi 愚 yú 敝 bì |

我 | I, the lowly/ignorant | Self-deprecating |

| 奴婢 nú bì 贱妾 jiàn qiè |

我 | I, your slave/servant/concubine | Self-deprecating (for women) |

| 汝 rǔ | 你 | you/thou | |

| 朕 zhèn | 我 | I/me | Used by an emperor for self-address |

| 贤 xián | worthy or virtuous person | Used to refer to someone respected | |

| 好汉 háo hàn | great man | Used to refer to a strong/courageous person | |

| 千夫 qiān fū | 群众 | a lot of people; the masses | |

| 百姓 bǎi xìng | 群众 | the common people; the masses |

Negation/affirmation expressions

There are tons of words used to express negative and positive meanings in Chinese. Sometimes, as in English, they can even express the opposite connotation (think double negatives). Here’s some common negatives and their usages.

| Word | Translation | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 非 fēi 未 wèi 无 wú 毋 wú 弗 fú |

not; non- | |

| 莫 mò 勿 wù |

do not | 切莫 (you must not) |

| 否 fǒu | to negate | Ex. 是否 (if; whether or not) |

| 免 miǎn | to avoid | Ex. 难免 (hard to avoid) |

Descriptors for time

Time of day

You should be at least familiar with the primary systems for telling time in historical China, which are heavily rooted in Chinese cosmology, mythology, and astrology. Simply put, there are two sets of ordinals (counting symbols like 1, 2, 3, etc) that are used for both counting and timekeeping: the Ten Heavenly Stems and Twelve Earthly Branches.

The Twelve Earthly Branches were used to divide the 24-hour day into 2-hour increments. If you’re familiar with the Chinese Zodiac, there’s some association as well — each of the 12 zodiac animals has a corresponding Earthly Branch.[1]

You don’t really need to know all the Earthly Branches, but I’ve included some of the most important ones in the table. A few, such as 午 (中午,下午) and 晨 (早晨) are still in common use today.

| Word | Translation | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 卯 mǎo | dawn | 4th Earthly Branch, 6am |

| 晨 chén | early morning | 5th Earthly Branch, 8am. Ex. 拂晨 (daybreak) |

| 午 wǔ | noon | 7th Earthly Branch, 12pm |

| 旦 dàn 晓 xiǎo |

dawn | Ex. 拂晓 (daybreak) |

| 夕 xī | dusk | |

| 昼 zhòu | daytime | |

| 昏 hūn | twilight | Ex. 黄昏 (dusk) |

| 暮 mù | sunset | |

| 傍晚 bàng wǎn | near nightfall |

Chronology and timespan

There are many literary ways of ordering events chronologically, expressing how much time has passed, or connoting the pace of events, like suddenly or slowly.[2]

| Word | AKA | Translation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 昔 xī | 以前 | in the past | Ex. 昔日, 昔年 (in times past; once upon a time) |

| 翌日 yì rì | 明天 | tomorrow | |

| 曾 céng | 以前 | once; formerly | Ex. 曾经 |

| 载 zǎi | 年 | a year | Ex. 半载 (half a year) |

| 晌 shǎng | 天 | a day | Ex. 半晌 (quite a while; lit. half a day) |

| 倏地 shù de 霍 huò 骤然 zhòu rán 乍 zhà 蓦然 mò rán |

突然 | suddenly | |

| 顿时 dùn shí | immediately | ||

| 霎时间 shà shí jiān 须臾 xū yú |

in a split second; in a flash | ||

| 顷刻 qǐng kè | 没过多久 | in no time; right away | |

| 之际 zhī jì | 的时候 | during; at the time of |

Counting

The first few of the Ten Heavenly Stems are still in modern usage as counting ordinals, especially in scientific settings, where they can function like the Greek alphabet’s alpha, beta, gamma, etc. Other words in this table may express repetition or multiplicity.

| Word | AKA | Translation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 甲 jiǎ | 第一 | first | 1st Heavenly Stem |

| 乙 yǐ | 第二 | second | 2nd Heavenly Stem |

| 丙 bǐng | 第三 | third | 3rd Heavenly Stem |

| 丁 dīng | 第四 | fourth | 4th Heavenly Stem |

| 屡 lǚ | repeatedly | ||

| 一番 yī fān | once | ||

| 兼 jiān | double; twice; dual | Ex. 兼备 (have both of two things) |

Religion

Journey to the West is a fantasy retelling of a real-life pilgrimage to India by the Buddhist monk Tang Sanzang to retrieve sacred Buddhist scriptures. Thus, the text is rife with religious vocabulary.

| Word | Translation | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 施主 shī zhǔ | benefactor | Used by a monk to address a layperson |

| 老衲 lǎo nà | I | Form of deprecating self-reference for an old monk |

| 修行 xiū xíng | to practice Buddhism | A general word to describe the overall practice of spiritual development, such as meditation and asceticism |

| 投胎 tóu tāi | reincarnation | |

| 轮回 lún huí | reincarnation | |

| 涅槃 niè pán | nirvana | |

| 报应 bào yìng | karma | |

| 因果 yīn guǒ | karma; cause and effect | |

| 苦海 kǔ hǎi | abyss of worldly suffering | |

| 浮屠 fú tú | stupa - a Buddhist temple | |

| 刹 chà | Buddhist monastery |

Death

Ways for embellishing or euphemizing death are common in any culture. Chinese is no exception; another student has collected 60 such words, and that isn’t even close to complete. I add some other important ones in the table below.

| Word | Translation | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 暴毙 bào bì | to die suddenly | |

| 成仁 chéng rén | to die for a good cause | |

| 舍身 shě shēn 牺牲 xī shēng |

to sacrifice oneself | |

| 驾崩 jià bēng | (of an emperor) to pass away | |

| 下地狱 xià dì yù | to descend to hell | |

| 见阎王 jiàn yán wáng | to see the King of Hell |

Misc Verbs/Adjectives

These are other random words that I think you should know.

| Word | AKA | Translation | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 料 liáo | 预料 | anticipate; expect | Ex. 未料 (unexpectedly) |

| 晓 xiǎo | 知道 | know | |

| 甘 gān | 愿意 | willing | |

| 照例 zhào lì | 按正常 | as usual; usually |

Hope this has been helpful!