Challenge 9 Implement PKCS#7 padding

As the challenge states, “A block cipher transforms a fixed-sized block (usually 8 or 16 bytes) of plaintext into ciphertext. But we almost never want to transform a single block; we encrypt irregularly-sized messages.”

The PKCS#7 padding scheme will append the number of bytes of padding to the end of the block. I use the pwntools pack() function to pack the number of padding bytes.

Challenge 10 Implement CBC mode

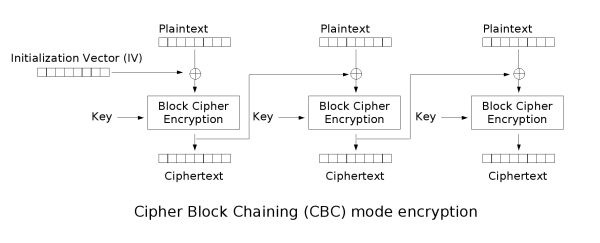

This challenge has us implement CBC mode of block encryption.

In CBC mode, each block of plaintext is XORed with the previous ciphertext block before being encrypted. We need an IV for the first block of plaintext.

In set2_utils, I create a CBC Cipher class that takes in a cipher and an IV. The encrypt() function will split the plaintext into blocks (usually size 16), and then do the encryption:

1 | # Xor with previous block. First prev_xor_block is the IV. |

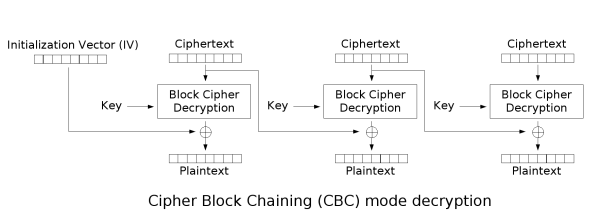

The decryption takes each block of ciphertext, decrypts it, and XORs with the previous block of ciphertext to recover the plaintext.

1 | for i in xrange(1, len(blocks)): |

I can verify I’ve done this correctly by decrypting 10.txt with a CBC Cipher with IV '\x00'*16.

Challenge 11 An ECB/CBC detection oracle

This challenge asks us to detect whether we’ve encrypted a text with ECB or CBC, chosen at random.

Recall the properties of ECB vs CBC — ECB will take two identical plaintext blocks and produce two identical ciphertext blocks.

This is as simple as asking the oracle to encrypt a string that contains at least two consecutive blocks of identical characters. If the oracle chooses ECB, the ciphertext will have two adjacent identical blocks as well.

To ensure that we have at least two consecutive blocks of identical characters, we need to input at least 43 bytes. Why? Because the oracle pads the plaintext with 5-10 bytes, so we need to give some offset to ensure our identical plaintext blocks are properly aligned.

R = random_nfix

1 | |--------16-----| |

Challenge 12 Byte-at-a-time ECB decryption (Simple)

I have an oracle that produces AES-128-ECB(your-string || unknown-string, random-key).

I can find unknown-string with this oracle. The idea is that,

- First, I need to find the block size of the cipher.

- Then, assuming I know it’s using ECB, I can find the flag byte-by-byte. How? Since I control my-string, I can ensure each time that the oracle encrypts 15 bytes that I know + one unknown byte. I can then create a table of all possible ciphertexts of the 15 known bytes + 1 unknown byte, and compare the ciphertext the oracle returns to the ciphertexts in my table.

To find the block size, I feed in incrementing offsets to the oracle, until the ciphertext length increases. The size of the increase will be block_size, because of the padding.

Next, I need to get an offset of 15 known bytes to feed into the oracle. The first offset is just 15 filler variables, all A’s.

1 | U = unknown flag byte |

And I create a table of all possible ciphertexts of A…U.

1 | for cand in candidates: |

I then feed the block with the unknown byte to the oracle, padding with the same filler variables as my offset. Perform the table lookup.

1 | oracle_block = oracle('A'*offset_len)[block_of_interest : block_of_interest + blocksize] |

At the next iteration, I decrease the number of filler variables by 1, since I have a known byte and want the next byte.

1 | Input to oracle, |-16-| bytes to be looked up in table: |

When I have 16 known bytes in this manner, I no longer need filler variables in my offset; I can just use the previous 15 known bytes as my offset. Note that my lookup table can be populated with ciphertexts of 16 flag bytes.

Since I have 16-byte ciphertexts in my lookup table, I need to first align, then get the index of, the 16-byte block-of-interest that I’ll look up in my table.

1 | Input to oracle, |-16-| bytes to be looked up in table: |

Stopping after I run out of bytes, I find the answer is

1 | Rollin' in my 5.0\nWith my rag-top down so my hair can blow\nThe girlies on standby waving just to say hi\nDid you stop? No, I just drove by\n |

Challenge 13 ECB cut-and-paste

Challenge 14 Byte-at-a-time ECB decryption with random prefix

In this challenge, a random-length prefix is added to the attacker-controlled string, AES-128-ECB(random-prefix || attacker-controlled || target-bytes, random-key). Thus, I need to know the length of the prefix to be able to conduct the same attack as Challenge 12.

Finding this length is not so hard.

- First, I can find the block index of the last byte of the prefix with just two calls to the oracle.

- Then, I find the offset of the last byte of the prefix within the last block.

1 | ciphertext1 = prefix_oracle('') |

Because this is ECB mode, the first different block between ciphertext1 and ciphertext2 will be the last block of the prefix.

1 | U = unknown flag byte |

Now that I know what block the last byte of the prefix is in, find_prefix_block_modulo_offset finds the offset of the last byte of the prefix. I want to align two blocks of identical plaintext, to encrypt to two blocks of identical ciphertext. The amount of offset I use to align will tell me the offset of the prefix.

1 | for i in xrange(0, blocksize): |

1 | |--offset-| |

, with offset_len always being 15 known bytes, as in Challenge 12.

The keys in my lookup table are no longer a fixed-length of blocksize — they include all known bytes now. Here, the len(offset) is not always 15, as in Challenge 12. Also, the length of my lookup table keys is not always blocksize; rather, the length of my keys increases with the number of known bytes. I could have implemented this more similarly to Challenge 12, which would have been less computationally expensive.

How do I produce ciphertext keys for my lookup table now? Here’s what I feed into the oracle:

1 | for cand in candidates: |

1 | |--lookup table key---------| |

1 | |-------------------lookup table key---------| |

Calling find_next_byte_with_prefix byte-by-byte, I find the same flag as before.

1 | Rollin' in my 5.0\nWith my rag-top down so my hair can blow\nThe girlies on standby waving just to say hi\nDid you stop? No, I just drove by\n |

Challenge 15 PKCS#7 padding validation

Here’s an easy one. We need only validate that the PKCS7 padding is correct.

1 | byte = s[-1] |

I check if the last pad_length bytes of s are equal to the string of byte repeated pad_length times, as it should be in a properly padded string.

Challenge 16 CBC bitflipping attacks

We have a function that takes user input and url-encodes special characters, and we want to exploit the properties of CBC to allow us to insert the string “;admin=true;” without the “;” and “=” being validated out.

Recall that CBC takes each block of ciphertext and XORs it with the next block of decrypted ciphertext to recover the plaintext.

If I can modify at least two consecutive blocks of ciphertext, I can make the second block decrypt to whatever I want.

I know that \x00 ^ \x59 = ; and \x00 ^ \x61 = '=' from ascii chart.

1 | user-controlled input: |

Done with set2!